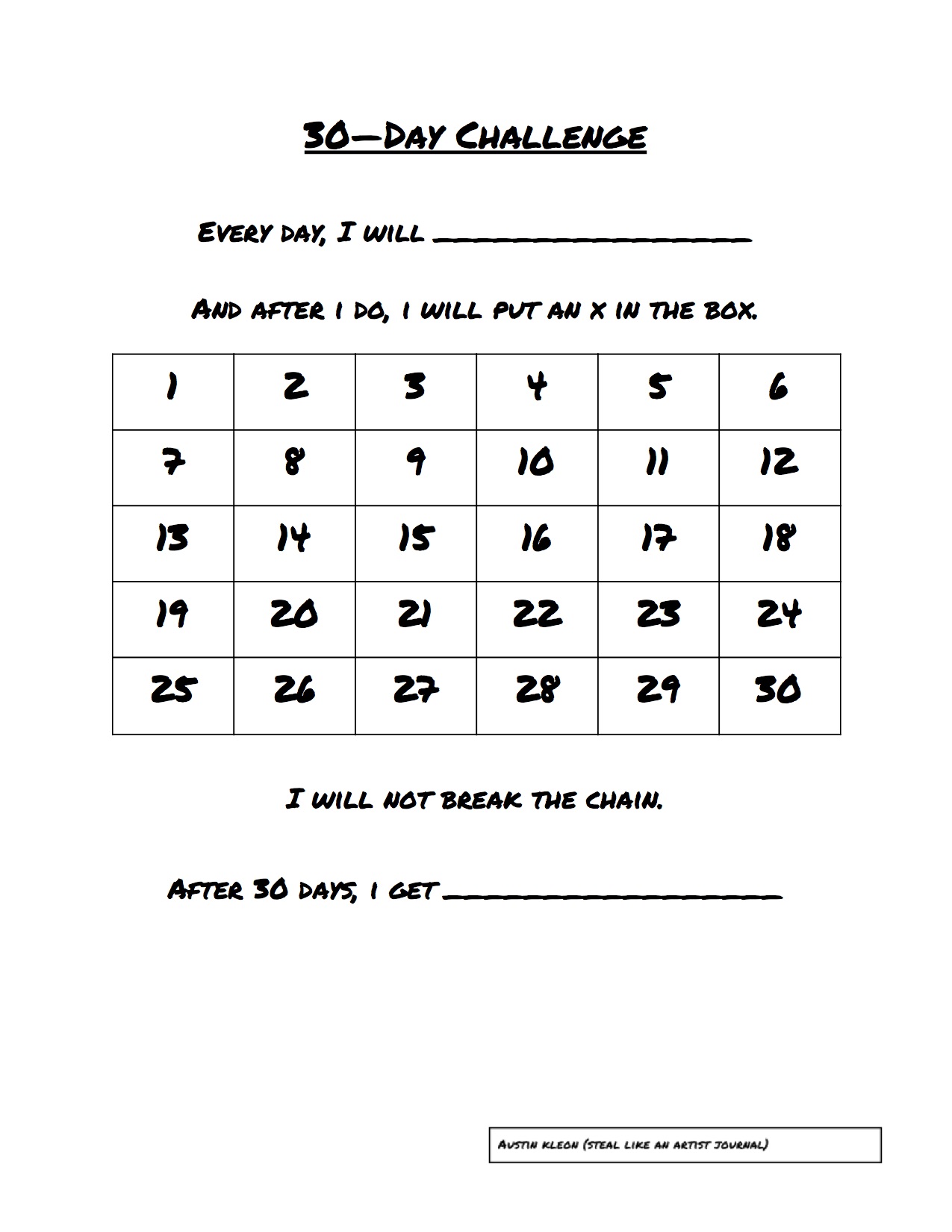

Several years ago I decided I was going to be a morning person. I’d read a ton of articles and blog posts that made me feel like a slouch for not getting up early enough. They had valid reasons why I should and warned of the opportunities I would be leaving on the table if I didn’t. I didn’t want to be one of those nuts that get up at 4 am, but I did want to start getting up earlier.

I set my alarm for 15 minutes earlier each day throughout the week, trying to train myself to get up at an earlier time. It was successful, at first. I had moved my wake up time back an hour after one week. Things were flying high and going well. No worries, no problems, and no obstacles. The first several weeks were a breeze.

I slowly crept back towards my previous wake up time as time past. I’d hit the snooze a time or two, or stay up too late the night before and have a good excuse for why I needed extra sleep. After a few months, I was back in my old routine without even noticing it.

How many times have we endeavored to establish better and more disciplined habits that didn’t take? How many times have we set goals to get up earlier, workout more or eat healthy without following through?

It’s been an all too regular occurrence in my life. I’ll set a goal, and even come up with a plan on how I’m going to make it happen, but too many of them end up as stories of failure. They haunt me. If I let them they tell me I’m a failure as well, and that I shouldn’t try to make changes to the life I lead. I should accept the status quo.

I can’t listen to those voices. I can’t listen to the weakness. They’re not telling the whole truth. There may be a kernel of truth in there somewhere, but it’s covered with lies. The truth is that I failed because I was missing the most important piece to the puzzle. Have you put together a puzzle only to realize you’re missing a few important pieces?

Unless you have kids, it may not happen to you often. But I’d lay down big money it happens all the time in the real world. You decide you’re going to do something, you consider the cost, and come up with a plan to get there. You invest time and work hard to see change occur, but it’s short lived. What happened? What was the missing piece to your puzzle?

You must know why you’re doing it in the first place if you’re going to have a chance at real lasting change. “Discipline without direction,” Donald Whitney said, “is drudgery.”

You must have a compelling reason and purpose for change to stick. ‘Want to’ isn’t enough, there must be a real, and powerful reason why you are endeavoring to change. It has to be a reason that forces you forward and pulls you through the hard times.

The vague promise of productivity wasn’t enough to get me out of bed, but getting up to workout and write has been. I’m actually getting up even earlier than I’d thought possible because I’ve found an irresistible motive.

Spend some time this week, thinking about the why behind your biggest goals. What would your life look like if you reached them? Move beyond the vague and focus on the specific. I trust that if you find a powerful purpose behind your goal, it’ll become that much easier to hit your target.