Few things are worse than reading a boring book. Your eyes begin to droop, your head nods and frustration builds. Each time you set it down, it becomes harder to pick up again. These are the books you either sludge through, or stop reading altogether.

“Writing,” Zinsser said, “is an intimate transaction between two people, conducted on paper, and it will go well to the extent that it retains its humanity.” Writers who fail to hold your attention, fail to come along for the ride. They remain distant, cold and impersonal. Ornate language and generalities hide them from view and you pay the price.

When I first picked up On Writing Well, I had low expectations. It was lauded as a must read for any aspiring writer, so I ordered it on Amazon. Books on writing however, sounded as though they would be unimaginative and dull. I pictured every English teacher or professor I’d ever had and assumed they would catalog the rules of grammar and syntax, consisting of half-hearted advice from half-hearted authors looking to make a buck. I never in my wildest imaginings, thought a book on writing would become one of my favorite reads.

“It’s far easier,” Zinsser said, “to bury Caesar than to praise him—and that goes for Cleopatra, too. But to say why you think a play is good, in words that don’t sound banal, is one of the hardest chores in the business.” That is where I find myself at this junction in our journey together. I find Zinsser’s work to be excellent, exciting and helpful, but grasp for the right words to convey why.

Often, we aren’t sure why we like one movie and not another, or why we enjoyed seeing this play instead of that one—at least that’s where I regularly find myself. In large measure it comes down to taste. I have a taste for Zinsser’s style, and an enjoyment for his use of language. Rather than tell you his book isn’t boring, I’d like to show you Zinsser in his own words. You’ll be in the best position to determine if his way of approaching the task of writing suits your interests far better than I can guess. In short, you'll be the judge if you find it boring.

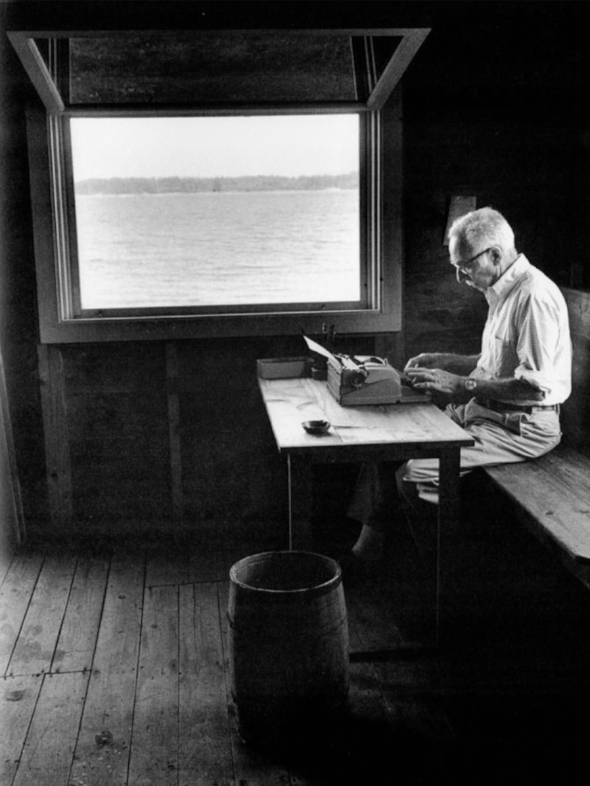

“A white haired man,” Zinsser describes, “is sitting on a plain wooden bench at a plain wooden table—three boards nailed to four legs—in a small boathouse. The window is open to a view across the water.” This opening scene describes a photograph of E.B. White, that used to hang in Zinsser’s office. Students and writers alike gazed at that image throughout his career. “What gets their attention,” Zinsser said, “is the simplicity of the process. White has everything he needs: a writing implement, a piece of paper, and a receptacle for all the sentences that didn’t come out the way he wanted them to.”

Writing is a simple task. You sit down, and put on paper the ideas and thoughts swirling in your mind. Nothing could be more straightforward, and yet few things are more difficult. You get paralyzed by the size of the task. It is enormous in its appearance. You want to say something valuable, something important, something people will like. You’re so wrapped up in the finished product, you can’t get going.

“Computers,” Zinsser continues, “have replaced the typewriter, the delete key has replaced the wastebasket, and various other keys insert, move and rearrange whole chunks of text. But nothing has replaced the writer. He or she is still stuck with the same old job of saying something that other people want to read.” For all the advances time and invention have produced, our world remains writing based.

Your tools are good thinking and the English language. How you use them is largely a matter of personal preference, but you can’t produce quality writing without putting both to work in service of your goal. “There isn’t a ‘right’ way,” Zinsser explains, “to do such personal work. There are all kinds of writers and all kinds of methods, and any method that helps you to say what you want to say is the right method for you.” Some people like to get up early and write, others prefer to stay up late. Some require silence, while others prefer music. Each writer’s approach is unique and personal. “It’s a question,” Zinsser explains, “of using the English language in a way that will achieve the greatest clarity and strength.”

“The essence of writing,” Zinsser said, “is rewriting.” Clarity and strength are achieved by tinkering with words, sentences and paragraphs until they are just right. The bulk of Zinsser’s book walks you through how to do just that no matter the subject before you. “Good writing is good writing,” Zinsser asserts, “whatever form it takes and whatever we call it.”

10 Favorite Quotes

“Clear thinking becomes clear writing: one can't exist without the other.”

“Rewriting is the essence of writing well: it's where the game is won or lost.”

“Eliminate every such fact that is a known attribute: don't tell us that the sea had waves and the sand was white. Find details that are significant.”

“So when you write about a place, try to draw the best out of it. But if the process should work in reverse, let it draw the best out of you.”

“No wonder you tighten; you are so busy thinking of your awesome responsibility to the finished article that you can't start.”

“My commodity as a writer, whatever I'm writing about, is me. And your commodity is you. Don't alter your voice to fit your subject. Develop one voice that readers will recognize when they hear it on the page, a voice that's enjoyable not only in its musical line but in its avoidance of sounds that would cheapen its tone: breeziness and condescension and cliches.”

“Find the best writers in the fields that interest you and read their work aloud. Get their voice and their taste into your ear—their attitude toward language. Don't worry that by imitating them you'll lose your own voice and your own identity. Soon enough you will shed those skins and become who you are supposed to become.”

“Moral: any time you can tell a story in the form of a quest or a pilgrimage you'll be ahead of the game. Readers bearing their own associations will do some of your work for you.”

“Be yourself and your readers will follow you anywhere. Try to commit an act of writing and your readers will jump overboard to get away. Your product is you. The crucial transaction in memoir and personal history is the transaction between you and your remembered experiences and emotions.”

I keep On Writing Well within arms reach of my desk. Whenever I begin a new project, I pull it down, flip through its pages and in so doing find the help I need to finish my task. It serves as both an inspiration and a resource regardless of the project before me.

"All the pieces of paper," Zinsser said, "that circulate through your office each day are forms of writing. Take them seriously." Much of what I do each day involves writing. As much as we live in a digital world, it remains a world comprised of words. The introduction of newer and newer technology only serves to increase the speed at which I am expected to perform the task of putting thoughts on paper. "Clear thinking," Zinsser said, "becomes clear writing: one can't exist without the other." Zinsser helps me accomplish both. He settles my mind, and gives me direction as I attempt to write.

Whether you have a blog, and idea for a book or simply desire to improve the quality of the emails you send, On Writing Well has something for you. “Banality,” Zinsser points out, “is the enemy of good writing: the challenge is to not write like everybody else.” Zinsser’s book will help you improve your writing and develop a style all your own.